Table of Contents

Extreme Programming

Extreme Programming (XP) is an Agile software development framework designed to improve software quality and responsiveness to changing customer requirements. Developed in the 1990s by Kent Beck, XP emphasises frequent releases in short development cycles, which improves productivity and introduces checkpoints at which new customer requirements can be adopted.

XP is centered around a set of core values:

- Communication

- Simplicity

- Feedback

- Courage

- Respect

These values guide XP teams to focus on collaboration, reduce unnecessary complexity, and maintain a close working relationship with customers to ensure the product aligns with their expectations. In XP, teams work in short, iterative cycles with customer feedback at every stage, allowing for quick adjustments based on real-world insights.

XP’s practices are particularly beneficial for projects with rapidly changing requirements or those that demand high reliability and performance. It is also highly suited to teams that thrive in collaborative environments and are committed to following disciplined engineering practices. By applying XP, teams can achieve faster delivery cycles, improved code quality, and closer alignment with business needs, making it a valuable approach within Agile development.

XP Practices

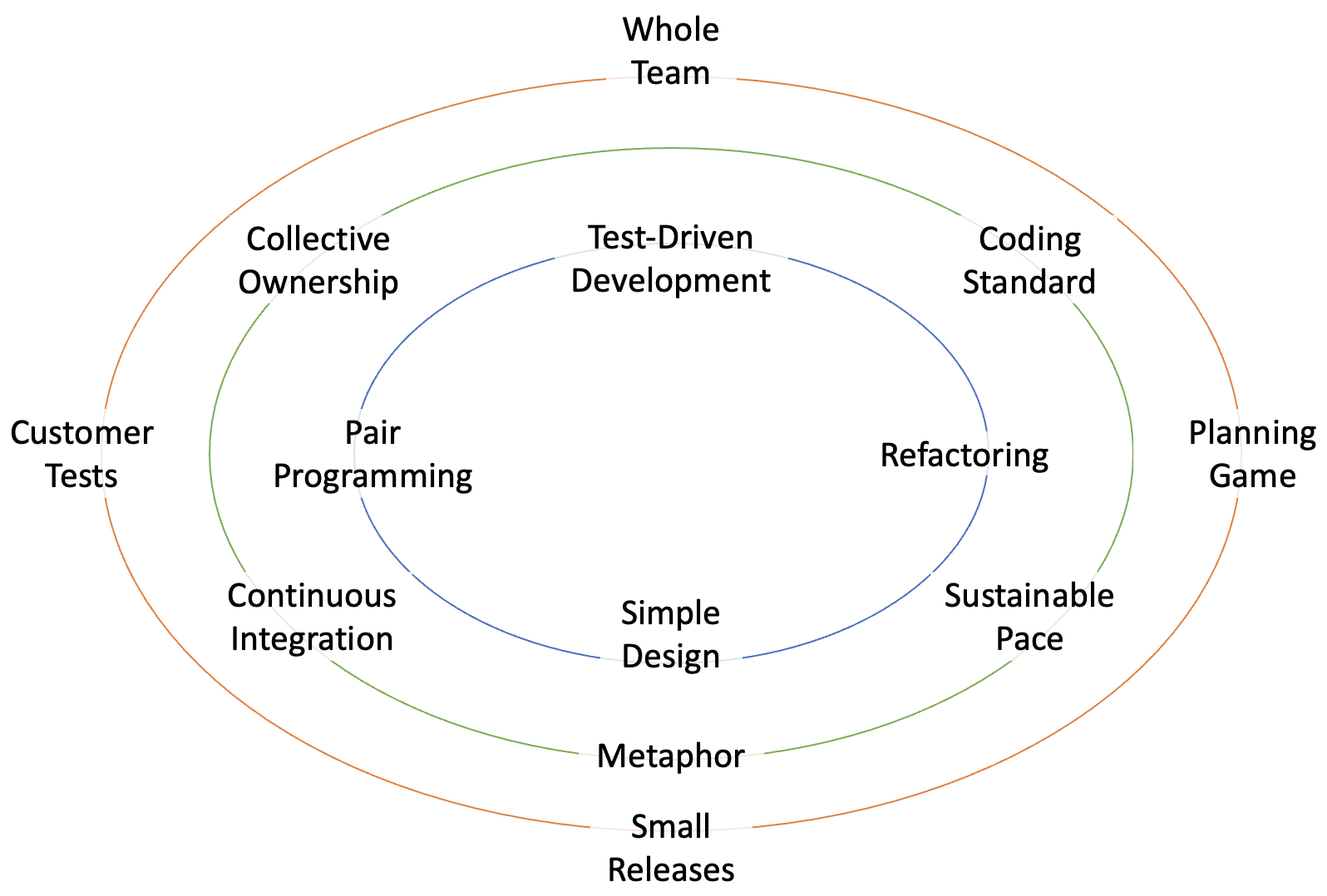

XP is commonly visualised as the collection of practices shown in Fig. 1. However, it is more than a loose collection of guidelines. It’s a disciplined, interconnected framework with a specific set of values, principles, and practices that work synergistically to support high-quality, responsive software development. Each practice in XP is carefully chosen and reinforced by other practices, creating a cohesive approach that is designed to address common challenges in software projects.

Some of the practices such as refactoring are covered elsewhere in these notes. The next few sections provide details on some of the others.

Pair Programming

Pair programming is a core practice in XP and other Agile methodologies that involves two developers working together on the same task, at the same workstation. In pair programming, one developer, known as the “driver,” writes the code, while the other, known as the “observer” or “navigator,” reviews each line of code as it’s written, offering suggestions and identifying potential improvements. The two developers swap roles frequently, ideally every 20-30 minutes, to maintain engagement and share knowledge. Theoretically, pair programming delivers

- Improved code quality

- Knowledge sharing and skill development

- Increased collaboration and team cohesion

- Reduced bottlenecks and dependencies

While pair programming can be highly beneficial, it may not always be suitable for every task or team. Pairing on repetitive or low-priority tasks, for example, may not justify the time investment. Also, if a developer is working on a task that requires deep concentration or independent exploration, solo work may be more effective.

Where pair programming is used, it needs to be implemented carefully and managed just like any other technique. Paired developers should have complementary skills, for example, and individuals should not be paired for too long to avoid “pair fatigue”. Rotating pairs also improves knowledge sharing across the whole team. While the developers are working together it is important to maintain control over the process by ensuring that the roles are clearly identified and that timing is properly observed. As well as swapping roles on a regular basis, the work should be timeboxed (e.g. 90 minutes) so that the pair gets regular breaks.

Using pair programming effectively takes some practice. Both members of the pair need to buy into the process. A skills imbalance can lead to poor communication, frustration and eventual dominance by one of the pair who tends to take the driver role more often. Some developers may feel uncomfortable working so closely with a partner, especially if they are used to working independently. In such situations, it can be useful to start with short, informal pair programming sessions and gradually increase their frequency and duration as team members get more comfortable. Clear expectations for collaboration are crucial, as is creating a safe, respectful environment where everyone feels valued.

Planning Game

The Planning Game guides the team in planning and prioritising work based on customer needs and the team’s capacity. It’s a collaborative process involving both the development team and the customer (or product owner) to establish what features will be implemented, in what order, and within what timeframe. The Planning Game helps ensure that development stays focused on delivering the highest-value features first, aligning closely with Agile’s customer-centric philosophy. In this context, the term game highlights the interactive and iterative nature of planning, where both customers and developers play specific roles, make strategic choices, and engage in a dynamic back-and-forth to reach a shared goal.

Like other games, the Planning Game involves strategic decision-making and negotiation. Customers prioritise features based on business value, while developers estimate feasibility and effort. Both sides negotiate a realistic plan that balances priorities and technical capabilities. This negotiation resembles the tactical aspects of a game, where both sides strategise to reach the best possible outcome within given constraints. The Planning Game is played in rounds — release planning and iteration planning — where each session builds on previous rounds, adjusting based on progress and changing needs. Like rounds in a game, each iteration allows the team to reassess and realign based on newly revealed information, making it an interactive, evolving process.

The main stages of the Planning Game are

- User Story Creation: User stories are written by the customer to express the product’s functionality.

- Prioritisation: The customer prioritises the user stories based on business value, which helps focus the team on the most impactful features first.

- Estimation: The development team estimates the effort required for each story using relative measures (such as story points) or time-based estimates. Estimations are usually kept rough in release planning but become more refined in iteration planning.

- Iteration Selection: For each iteration, the customer selects a set of user stories to be completed, working within the capacity of the development team. Developers commit to delivering these stories by the end of the iteration.

- Review and Adjust: At the end of each iteration, the team and customer review progress, adjust priorities as necessary, and plan the next iteration, allowing flexibility for evolving requirements.

Just as with pair programming, or any other technique, there may be situations where the Planning Game is not the best approach. To take a simple example, it is not possible to produce valid resource or time estimates if the project requirements are not sufficiently clear. Other requirements elicitation techniques should be used to elaborate the requirements to the point where accurate estimation is possible. Another potential problem situation is where the customer is not fully engaged in the process. To be effective, the Planning Game requires both the Customer and Developer roles to be filled. Trying to use the Planning Game with only the developers means that there is no negotiation and no trade-offs between business goals and technical feasibility.

Metaphor

the concept of metaphor is used in XP as a shared story or analogy that represents the structure and function of the system being developed. It’s a simple, understandable mental model that helps the entire team — developers, customers, and other stakeholders — visualise how the system works and how its components relate to each other.

The metaphor serves as an alternative to formal architectural documentation by providing a relatable, high-level description of the system’s design that anyone, regardless of technical expertise, can understand. It’s a tool for communicating complex technical concepts in an accessible way, which supports alignment, consistency, and collaboration across the team.

Some examples of development metaphors are listed below.

- Digital Library System as a “Bookshelf”: In a system designed to manage digital resources, the metaphor could be a “bookshelf,” where different categories of resources (books, magasines, newspapers) are “shelves” that organise the data. This metaphor can help the team visualise how resources are stored, organised, and retrieved.

- E-commerce Platform as a “Marketplace”: In an e-commerce system, using the metaphor of a “marketplace” can represent different entities like “sellers” (merchants), “products” (items for sale), and “shoppers” (users), making it easy to understand the roles and interactions between these components.

- Airline Booking System as a “Travel Agency”: In a flight booking system, the metaphor of a “travel agency” can represent different elements, like flights as “itineraries” and customer bookings as “reservations,” helping simplify how users interact with the system.

The metaphor acts as a high-level mental model that supports communication, simplifies complexity, and guides design. By offering a relatable analogy for the system’s structure and behavior, the metaphor helps all team members maintain a consistent understanding of the project, ultimately leading to more cohesive development and collaborative alignment. However, they can sometimes oversimplify or fail to represent complex systems accurately. In cases where the system requires highly technical detail or has intricate dependencies, the metaphor may need to be supplemented with additional documentation or architectural models.

Roles

As well as the Developer and Customer roles, XP provides for several other roles that are described below.

Coach

The coach in an XP project serves as a mentor and facilitator who guides the team in effectively implementing and adhering to XP practices and principles. Unlike a traditional project manager, the coach focuses on process over control, helping the team maintain discipline in core XP practices like Test-Driven Development (TDD), Pair Programming, and Continuous Integration. The coach works closely with the team to identify obstacles, resolve conflicts, and encourage open communication, fostering a collaborative and productive environment. Additionally, the coach supports continuous improvement by conducting retrospectives, providing feedback, and helping team members reflect on their work to refine practices. Through their guidance, the coach ensures that the team remains aligned with XP values, delivers high-quality code, and responds flexibly to changing customer needs.

Tracker

The job of the Tracker is to monitor the team’s progress, identifying obstacles, and providing insights into the project’s trajectory. The Tracker gathers data on metrics like story completion, velocity, defect rates, and any other indicators that reveal the team’s productivity and quality levels. By analysing this information, the Tracker helps the team recognise patterns, manage workload, and adjust processes to optimise efficiency and maintain a sustainable pace. The Tracker also assists in iteration planning by highlighting areas where the team is excelling or struggling, offering a fact-based perspective that supports better decision-making. Ultimately, the Tracker’s role is to ensure transparency, support continuous improvement, and enable the team to meet its goals consistently.

Tester

It is the Tester’s responsibility to ensure the quality of the software under development and alignment with customer expectations. The Tester collaborates closely with the customer and developers to define and create acceptance tests for each user story, clarifying what constitutes a completed and functional feature. By developing automated tests and running continuous checks, the Tester helps identify issues early, preventing defects from reaching production. They work with developers to ensure that each iteration delivers a high-quality, reliable product by validating that new features meet requirements and that existing functionality remains intact. Through continuous testing and feedback, the Tester contributes significantly to the XP team’s goal of delivering software that is both functional and stable, building confidence in the final product.

Manager

the Manager plays a supportive role focused on resource coordination, facilitating team needs, and addressing any logistical or administrative challenges that arise. Unlike a traditional command-and-control manager, the XP Manager acts as a facilitator, ensuring the team has the tools, information, and environment required to function effectively. They handle external dependencies, communicate with stakeholders outside the team, and shield the team from unnecessary interruptions, allowing developers to stay focused on their work. Additionally, the Manager may assist in prioritising work alongside the customer, balancing business goals with technical considerations. Their role is to create a productive, supportive environment that enables the XP team to follow Agile principles and maintain a sustainable pace, helping to keep the project aligned with both team capabilities and customer expectations.

Whole team

In XP, the entire team can be considered a cohesive project role because the team collectively takes responsibility for the project’s success, with each member contributing their unique expertise to achieve shared goals. Rather than working in silos, the XP team operates as a single, collaborative unit where roles like developers, testers, the customer, and the coach contribute to both decision-making and project execution. This collective approach ensures that everyone has a stake in each part of the process—from defining requirements and estimating effort to coding, testing, and delivering value.

The XP team as a whole embodies key XP values such as communication, simplicity, feedback, courage, and respect. By working together closely, team members ensure transparency, address issues collaboratively, and create a shared understanding of the project’s goals. This alignment enables the team to self-organise, respond flexibly to changes, and support each other in maintaining quality standards, meeting deadlines, and continuously improving. Thus, in XP, the team itself functions as an integrated role that unites individual contributions toward the project’s success, with shared ownership over both the process and the product.