Workflow

When you are working on a string of similar tasks using the same tools it can get a bit boring. A natural tendency is to internalise short and reliable patterns for getting the work done. Perhaps it involves remembering to save your work at a particular point before going on to the next step, or creating stub tests as you go along so that you don’t have to think too hard later on. As time goes on, you can reach the point where you just do these things on autopilot. What you are doing is creating and maintaining a workflow. Just as with design patterns and many other aspects of software development, the way you organise your work is up to you. If you are working alone, creating your own workflows is convenient, but in a team situation it becomes vital going far beyond simply alleviating the boredom of repetition.

One of the issues that needs to be addressed in a team context is that different people prefer to do things in different ways. That is OK up to the point that it starts to reduce the overall efficiency of the team effort. That can occur for example if one person on a team fails to take into account someone else’s needs. In that case, something does not get done at the most efficient moment, and time is lost later. Another case is where a developer finishes the task they are on but fails to update the documentation or let the rest of the team know that the task is complete. The solution to these and many other types of communication and coordination issues is to establish team workflows and to make sure that the whole team sticks to them.

)](https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/team_chat.png)

A software engineer makes a personal contribution to a project through the application of good programming practice and the adherence to the agreed workflow of the team. Once a development task is complete, it is committed to the code repository where it is reviewed by another developer. Once the comments are addressed, the modified code is merged with the main codebase.

After merging, further quality checks are performed which focus on the operation of the entire system including the new code changes. The pre- and post-merge checks are summarised in Fig. 2.

graph LR

subgraph pre-merge

id1([Impact analysis]) -->id2([Self-review])

id2 -->id3([Unit testing])

id3 -->id4([Static code analysis])

id4 -->id5([Rebase and check for conflicts])

id5 -->id6([Code review])

end

pre-merge:::phase-->id7([Merge])

id7:::commit -->post-merge:::phase

subgraph post-merge

id8([Build verification test]) -->id9([Integration test])

id9 -->id10([Dynamic code analysis])

id10 -->id12([New feature & <br/>regression testing])

end

classDef default fill:#299ef3,stroke:#333366,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

classDef commit fill:#f37e29,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

classDef phase fill:#fafafa,stroke:#333366

Fig. 2: Code quality analysis techniques (Adapted from Cap Gemini, n.d.)

Impact analysis

Impact analysis is the process of assessing the potential consequences of changes made to a software system, particularly in terms of how they will affect the rest of the system. In collaborative software development impact analysis helps developers understand the scope of the changes they are introducing, identify dependencies, and anticipate potential side effects that could affect other parts of the system. The goal is to make informed decisions and minimise unintended consequences, such as introducing bugs or breaking existing functionality. This could involve, for example, understanding how changes to a method, class, or module impact related classes, the broader application architecture, and other parts of the system, such as external dependencies, databases, or user interfaces.

Although it only appears in one place in Fig. 2, impact analysis should ideally be conducted at several key points throughout the software development process to ensure that potential risks and side effects of changes are identified early and mitigated effectively. Other times when impact analysis would be appropriate include

- During design and architecture planning

- During code reviews

- Before merging code into main branch

- After detecting a bug or issue in testing

- Before deployment or release

- After receiving feedback from production

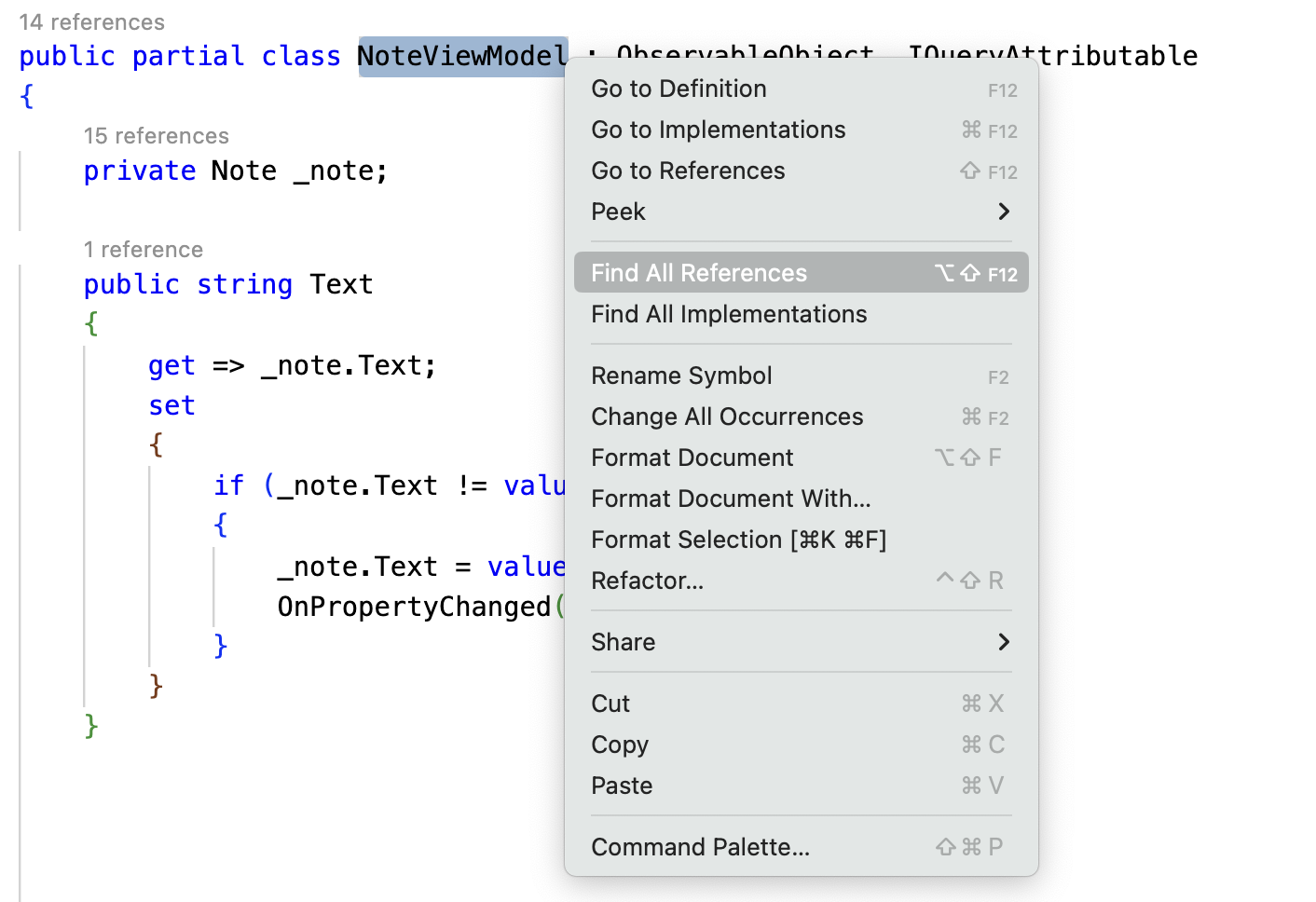

From a practical point of view, impact analysis involves some general activities such as investigating the scope of the change, its dependencies and interactions with external interfaces. It is also important to remember that test code may need to be updated and that the security implications of the change should be actively considered. A good place to start is your IDE which provides a way to find the usages for classes and functions in the rest of the codebase. Fig. 3 provides an illustration from Visual Studio Code where there is a count of usages in a note before the class definition and a way to find all the usages via the context menu.

Key Considerations for C# Projects

- Type Safety: C# is a statically-typed language, which means that some potential issues (like method signature changes or type mismatches) can be caught by the compiler. Take advantage of this by ensuring the code compiles cleanly after changes, as compilation errors often indicate potential impacts on dependent code.

- LINQ and EF Queries: Changes to database models or queries (e.g., using Entity Framework or LINQ) can have a wide-reaching impact on how data is retrieved and manipulated in the system. Be sure to assess whether changes in these areas could affect performance or the correctness of data retrieval.

- Use of Interfaces: C# projects often rely on interfaces and dependency injection (DI). When making changes to interfaces or their implementations, consider how those changes will affect all dependent classes, especially in systems using DI frameworks like ASP.NET Core.

- Asynchronous Programming: If you’re changing asynchronous code (using async/await), consider how those changes might impact application performance or behaviour, such as handling exceptions or concurrency issues.

Static analysis

When carrying out a code review, the ideal approach is to include two steps. The first is to examine the code in an editor to try to identify potential improvements, and the second is to run the code to check that it behaves as expected. The first of these can be thought of as static analysis because you are examining the code in isolation. The second activity can be considered dynamic analysis since the code is actually in operation and you are evaluating its behaviour.

Development tools such as Visual Studio perform static analysis on the code as you write with the results presented in various ways. For example, lines of code that contravene a style rule might be underlined or have a light bulb icon appear against them, for example. The IDE may offer to reformat the code automatically if the resolution is a simple one. Structural issues identified by the built-in code analysers may be indicated by a different highlight or a different icon such as a screwdriver. Again, the IDE may offer a range of solutions, but in the structural case, they affect the code itself and not just the way it is formatted. These resolutions therefore constitute code refactorings.

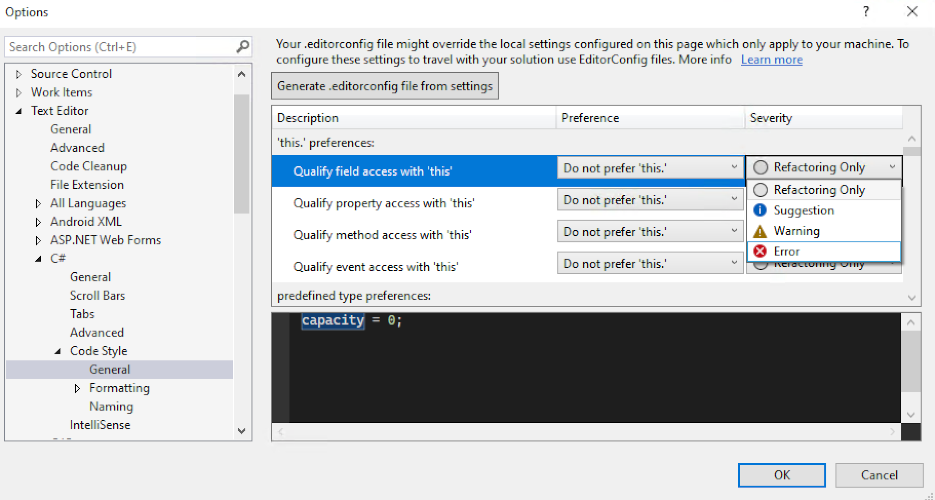

The default rules that are built into an IDE can be configured by changing the options settings. A rule could be disabled, for example, so that the highlights and warnings no longer appear. Alternatively, the severity of the rule might be increased so that the IDE treats it as an error rather than a warning as illustrated in Fig. 4.

It is very common for developers to ignore any warnings generated by the IDE since they do not affect the operation of the code. They are therefore treated as insignificant. However, in a team situation where future maintainability and general code quality are major concerns, every software engineer should aim to resolve any parts of their code that produce warnings. Any rules that are not required can be disabled for the whole team, and the remainder can be configured so that their severity level reflects the team’s requirements.

When the default rules are not sufficient for a team’s needs, other tools such as StyleCop can be added to the IDE. In Visual Studio, this is done using the NuGet package manager. StyleCop provides greater control over code style with selectable rule sets. It is also possible to manage the rules as described above and to create custom rules as needed.

The main point of this section is that the warnings and suggestions generated by an IDE need to be treated as a useful tool to help ensure code quality rather than annoying background noise. Once the rules are appropriately configured, they provide vital information to the software engineer that should not be ignored.

Post-merge checks

These are often handled in the CI/CD pipeline and refer to system-level considerations rather than the details of any specific change as described below.

Build verification test

Verification that the entire application builds when the code changes are included

Integration test

Verifies that the entire application performs as intended when the code changes are included

Dynamic code analysis

Consists of checks that are performed while the application is running. This can include checks on external properties such as performance efficiency, but also provides a mechanism for checking for runtime errors. These might be caused by dependencies that cannot be checked statically such as instances of reflection, dependency injection, etc.

New feature and regression testing

Here, new system-level tests are developed for any new features, and the behaviour of the rest of the system is compared to previous results to ensure that it has not been adversely affected by recent changes.

Procedural conventions

GitHub and similar platforms provide an intuitive interface for managing collaborative code development. However, they also provide a lot of freedom to use the tools in different ways. For example, when a developer issues a PR, the system can suggest an appropriate reviewer based on activity data. This may be appropriate, but a team may want to intervene in this default process for various reasons. For example, the team may include people with different levels of experience and it may be appropriate that only the experienced people are asked to perform reviews.

A similar question arises with merge operations. The default case is that the original developer eventually merges the feature branch with the main branch. If there are code conflicts that need to be resolved manually, then it is the developer who is responsible for doing that. This is a potential risk to the main branch, and the team may decide that only certain people should be allowed to resolve this type of conflict.

Each team will have slightly different requirements, and these questions need to be answered by creating an explicit procedure in the team’s documentation.

Editors and IDEs

Development tools have had more than half a century to mature. Current editors and integrated development environments (IDEs) offer many features that help the software engineer to keep on top of the huge range of concerns when building high quality code. The main options are the smart editor (such as Visual Studio Code) and the IDE (such as Visual Studio).

The smart editor strategy can be considered bottom-up: its central function is editing code, and additional functionality can be included as extensions. The advantages are that its disk and memory footprints are kept as small as possible, and the working user interface is simplified. Its disadvantage is that it requires customisation for each distinct working environment, and some features require external configuration. Because this working environment is a collection of loosely-coupled modules, it is not as stable as the IDE approach.

The IDE strategy seeks to put all the tools the software engineer might need at their fingertips by integrating them into a single software application. Because a lot of functionality is included by default, its storage and memory footprints are much larger than those of a smart editor, and the interface is more complicated because there are many more options available. The main advantages of an IDE are its comparative stability, the lower maintenance overhead and the availability of advanced features such as package management.