Issues

Issues are a powerful tool for managing tasks, bugs, and feature requests in a software project. Mastering the basics of creating, labeling, assigning, and collaborating on issues will help you stay organised and contribute effectively to your team. Understanding how to track progress, link work, and participate in discussions about issues is essential for any developer working in a collaborative environment.

Issue creation

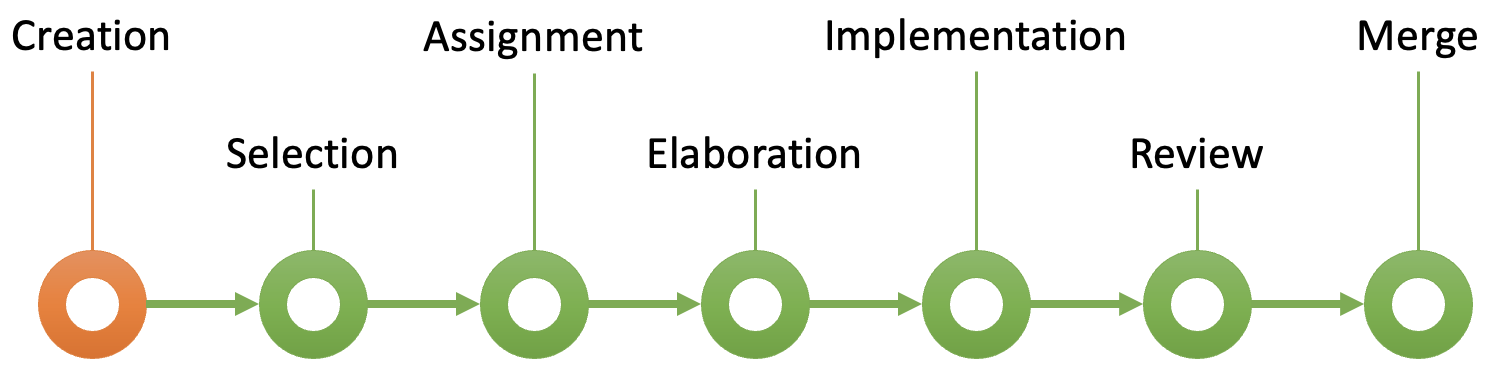

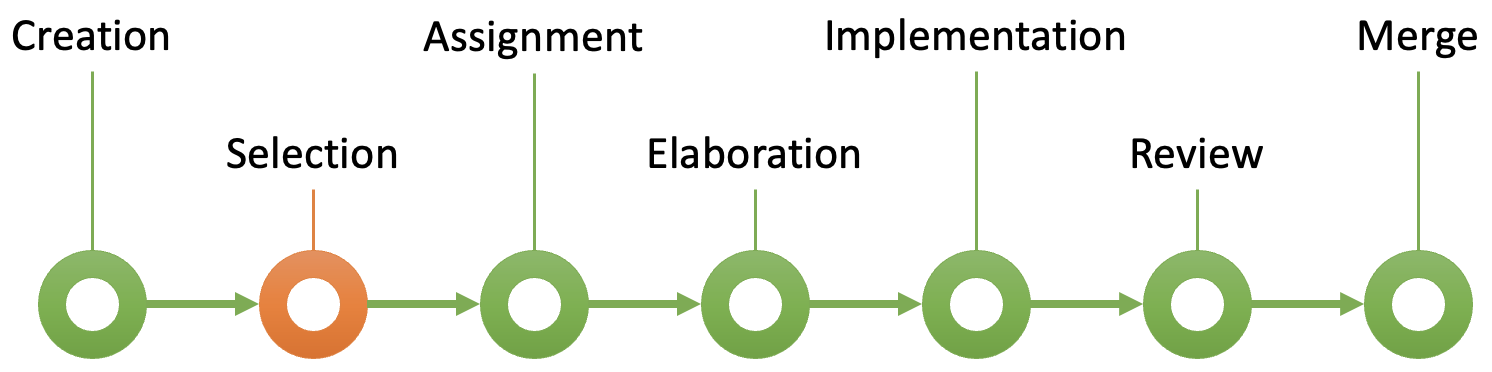

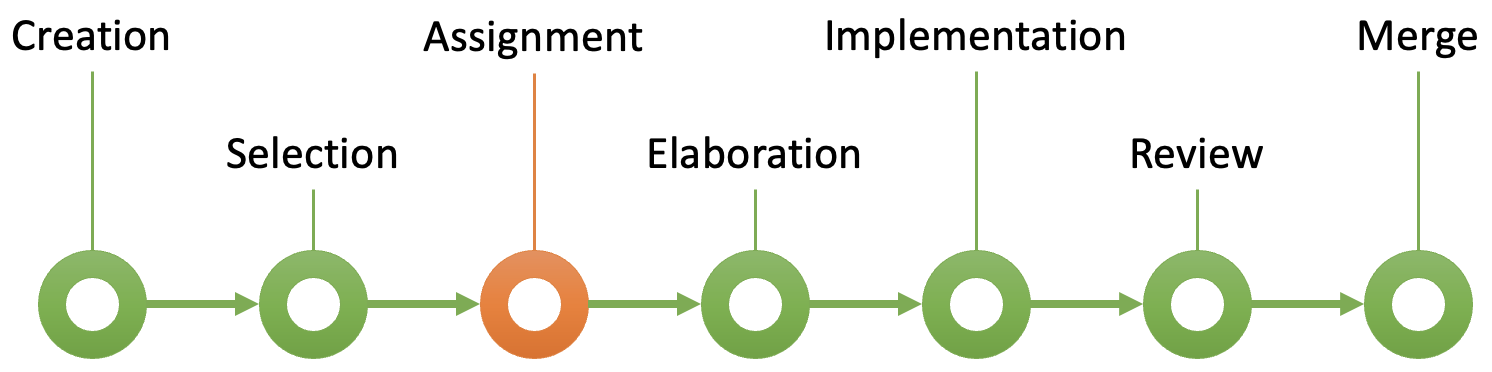

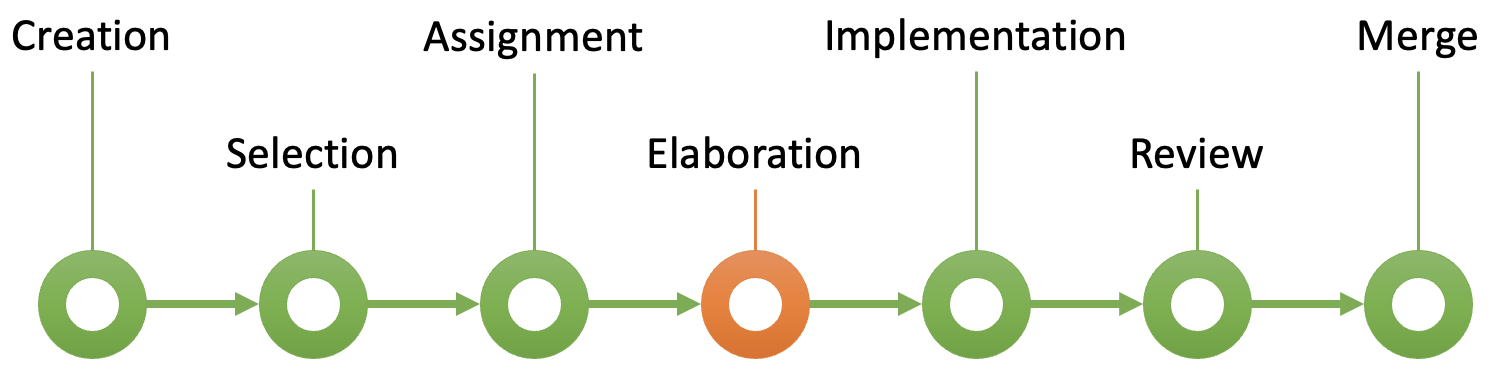

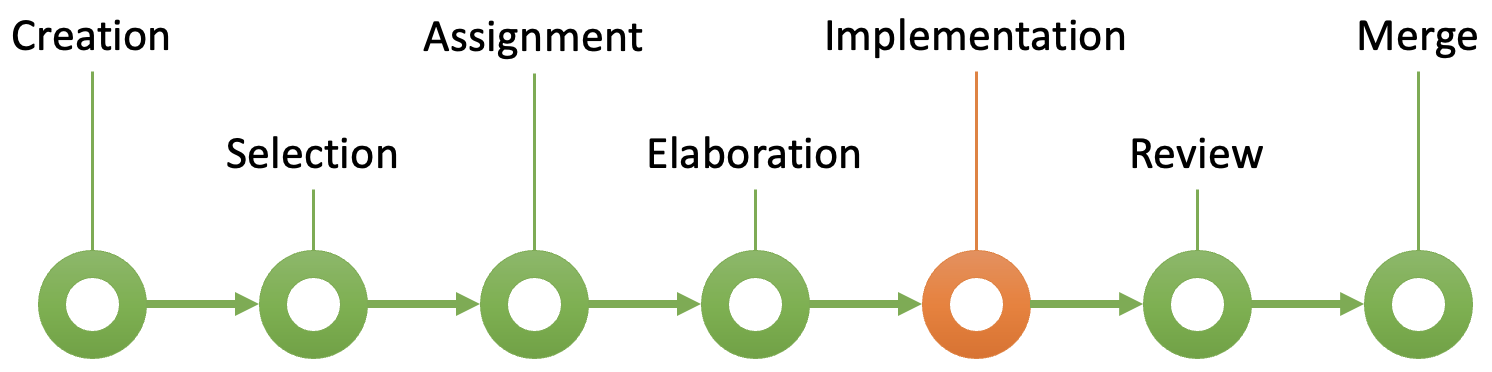

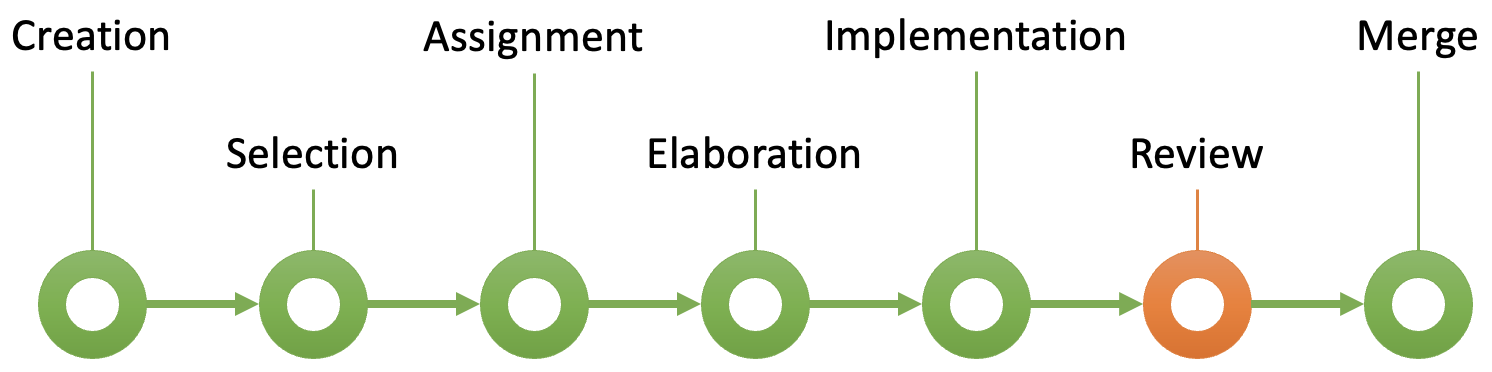

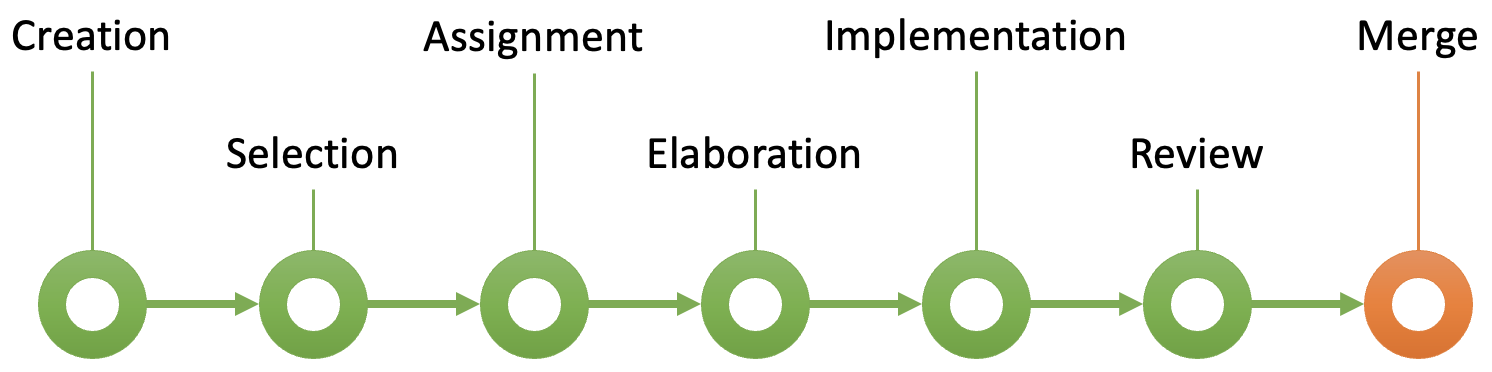

The lifecycle of an issue tends to follow the pattern shown in Fig. 1.

Issues are created for various reasons, each helping to track different aspects of the development process. During an initial development project to build a software product from scratch, the main source of new issues is the initial analysis work that produces a set of user stories. Even in a development project, though, issues are created in a variety of situations:

Issue selection

The set of open issues associated with a repository is commonly referred to as the issue backlog. This term is used to describe all the open issues that need to be addressed, including bugs, feature requests, tasks, and other tracked work. The backlog helps teams organise and prioritise the issues that are pending resolution. In Agile or Scrum projects, this backlog may be further refined into sprints or milestones. Issue selection refers to the process of choosing which issues from the backlog will be included in a particular sprint.

Issue assignment

Issue assignment is the process of designating a specific person or team to be responsible for resolving or working on an issue in a software development project. By assigning an issue, the project team ensures that someone is accountable for addressing it, which helps organise the workload, distribute tasks efficiently, and track progress within the project.

Once an issue is assigned there are some key points to be aware of:

- Ownership: When an issue is assigned to a developer or team, it becomes their responsibility to work on resolving the issue, whether it’s fixing a bug, developing a new feature, or completing a task.

- Accountability: Assignment helps project managers or team leads hold developers accountable for specific tasks, making it easier to track who is responsible for each part of the project.

- Collaboration: Issue assignment is often part of collaborative workflows in software development projects, ensuring that tasks are distributed appropriately and no work is overlooked.

- Tracking: On platforms like GitHub, GitLab, or Jira, an assignee can be tagged within the issue, making it easier to follow up on progress and review updates.

Issues are typically assigned manually by a project maintainer, team lead, or even by developers who assign themselves to an issue. Some tools and systems allow for automated issue assignment based on predefined rules, like distributing issues evenly among developers or assigning specific types of issues to specialised team members. Once an issue is assigned, the responsible developer will usually update the issue’s status as they work on it, and provide feedback through comments or commits linked to the issue.

Issue elaboration

Issue elaboration refers to the process of expanding and clarifying the details of an issue in a software development project to ensure it is well-defined and actionable. This typically involves providing a thorough description, context, and specific requirements related to the issue, such as the problem it addresses, steps to reproduce a bug, expected behaviour, or technical details for a feature request.

The goal of issue elaboration is to ensure that developers, testers, and other stakeholders fully understand the scope, requirements, and priority of the issue before any work begins. Well-elaborated issues help streamline development by minimising confusion and the need for back-and-forth clarifications.

Issue decomposition

If it becomes clear during issue elaboration that the issue is too large to address in one go, the developer should break the issue down into smaller, manageable tasks. This process, known as issue decomposition, helps ensure that each task can be handled independently, improving focus, efficiency, and clarity. In such a situation, the developer needs to:

As an example, consider an original issue is “Build a User Authentication System”. The developer might break it down into subtasks like:

- Implement User Registration API

- Implement User Login and Logout

- Set Up Password Recovery

- Integrate Frontend with Authentication API

- Write Unit Tests for User Authentication

Each of these subtasks can be tackled individually, making the overall task more manageable.

Key Elements of Issue Elaboration

Description:

A clear, concise explanation of the issue, including what needs to be done or what problem is being addressed. For bug reports, this might include the error encountered, while for feature requests, it might describe the desired functionality.

Steps to Reproduce (for Bugs):

A detailed list of steps that can reliably reproduce a bug, ensuring developers can replicate the issue before fixing it.

Expected vs. Actual Behaviour:

A description of the behaviour that is expected compared to what is currently happening, especially for bug reports.

Technical Specifications:

Any technical details required to address the issue, such as dependencies, relevant code snippets, database structures, or integration points.

Acceptance Criteria:

Specific conditions that must be met for the issue to be considered resolved or completed. These criteria help developers know when their work is done and allow testers to verify the outcome.

Priority and Severity:

1

2

> Information on how critical the issue is to the project. For example, high-priority issues may

> require immediate attention, while low-priority ones can be handled later.

Screenshots or Error Logs:

Visual aids, error logs, or other supporting materials that provide additional context to help diagnose or explain the issue.

Definition of Ready

It is a simple observable fact that the majority of developers like to get started working on code changes as quickly as possible. However, that is not always the most efficient approach and it can lead to dead ends, delays and re-work. To counter this, a Definition of Ready (DoR) can be used. Essentially, it is a checklist that defines the criteria for starting on a development task. The DoR is closely related to the key elements of issue elaboration and might include items such as:

- Requirements are clear

- Requirements are testable

- Acceptance criteria are defined

- Dependencies have been identified

A good way to decide whether a development task is ready to be worked on is to use the INVEST method:

Independent: It should be possible to work on a task independently of any other

Negotiable: A task should not be over-constrained; instead, there should be room for negotiatioon about the best way to implement it

Valuable: The value of the task for the project/client should be clear. This is usually captured by acceptance criteria

Estimable: It should be possible to make a reasonably accurate estimate of the time required for the task. If a task is too complex this will be difficult and the task may need splitting.

Small: (See previous point) Ideally a single task should represent a few person-days of work.

Testable: Another indication that a task needs to be split is when the tests required are hard to define or are very complex.

Implementation

Software development happens during the implementation stage of the issue lifecycle. the main activities are:

- Writing the Code: The core part of issue implementation involves writing or modifying the code to address the issue. For feature requests, this means building new functionality; for bugs, it involves fixing the defect; for technical debt, it may involve refactoring the code.

- Testing the Solution: In parallel with writing the code, the developer tests the solution. This could include running unit tests, integration tests, or performing manual tests to ensure the issue has been correctly addressed without introducing new problems.

- Committing Changes: A developer should commit changes to the local repository at logical and meaningful points during the development process. Committing regularly helps maintain a clear history of the work being done and provides a way to revert to a previous state if needed. Some commits may mark the end of a logical piece of work, for example, while others may be more preventative such as in advance of a major refactor.

Best practices for committing code includes

- Making small, frequent commits: Avoid committing too much at once. Break down your changes into small, manageable pieces to make the history more readable and debugging easier.

- Writing descriptive commit messages: Clearly explain the purpose of each commit. Descriptive commit messages make it easier for others (and your future self) to understand what changes were made and why.

- Avoiding committing broken code: Try to avoid committing code that doesn’t work or doesn’t pass tests, as this could disrupt the progress of others working on the project.

- Committing often, but only meaningful changes: Committing frequently is important, but ensure that each commit represents a logical step forward in the development process.

Definition of Done

Mirroring the Definition of Ready at the start of the process, the Definition of Done (DoD) is a clear and shared agreement among a development team on the specific criteria that must be met for a task, feature, or user story to be considered complete. It ensures that the work meets the necessary quality standards and is ready for release or the next stage of development. An example of a simple DoD might be:

- Code Complete: All code for the task/feature has been written, and no functionality is left unfinished.

- Code Reviewed: The code has been reviewed by at least one other team member and any feedback or suggested changes have been addressed.

- Tests Written and Passing: Unit tests and/or integration tests have been written for the new functionality. All tests pass, and there are no failing or skipped tests.

- No Critical Bugs: The feature has been tested, and no critical bugs or major issues remain. Any existing bugs have been logged and are being tracked for future fixes if not critical.

- Meets Acceptance Criteria: The task or feature meets the original acceptance criteria as defined in the user story or issue.

- Documentation Updated: Any necessary documentation (such as API docs, user guides, or inline comments) has been updated to reflect the new functionality.

- Deployed to Test Environment: The feature has been deployed to the test environment, and QA testing is complete.

- Performance Verified: The feature performs as expected, and there are no significant performance regressions or bottlenecks.

Review

A review is important when a developer finishes work on an issue because it ensures the quality, correctness, and maintainability of the code before it is merged into the main codebase. Code reviews provide an opportunity for peers or team members to evaluate the developer’s work, identify potential problems, and offer improvements.

Code review is covered in detail in its own section of these notes.

Merging

When the development and testing are complete, the code has been reviewed and any points arising from the review have been dealt with, the updated code can be merged with the rest of the codebase. GitHub and similar platforms provide functions that automate this process as much as possible, but occasionally there may be a conflict that requires attention from a human developer. One of the main techniques for handling this kind of problem is branching which is covered in its own section of these notes.

Summary

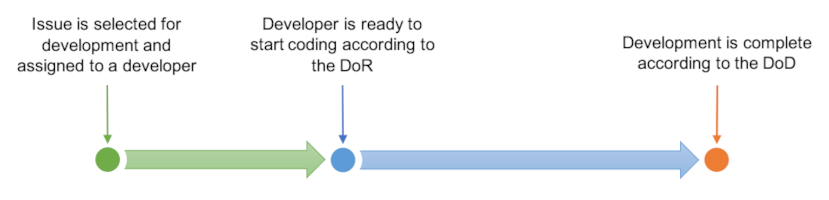

In light of the previous sections, two main phases of activity can be identified around any piece of development work as shown in Fig.8. The time required for each stage depends on the complexity of the original issue.

The rules that a team sets for itself in defining a standard workflow are intended to help with communication and to avoid errors and conflicts. Although there are examples of good practice available, there is no gold standard - each team needs to define its own specific workflow. Some steps are entirely procedural in the sense that they are the responsibility of the individual developer and cannot be automated. Others are made trivially easy by using the digital tools available. It must be stressed, however, that the team workflow needs to be actively managed. If assumptions are made about how team members will behave, serious difficulties may arise if they do not behave as expected. It is also tempting to try to define a complicated workflow from the outset in order to keep tight control over the project. This can be counter-productive, however, making the workflow difficult to understand. A good approach is often to set up a relatively simple workflow using default or standard options,and then to introduce changes when it becomes clear that the workflow can be improved.