Code reviews

The code review is a crucial part of the software development process for several reasons.

- It directly checks the quality of code being produced and enhances its quality

- It is a method for educating less experienced developers in the organisation’s expectations

- It provides a feedback mechanism through which organisational expectations can evolve over time

Like any other procedural operation, the effectiveness of a code review depends on the diligence of the reviewer. It would be very easy to approve every code change without examining it in detail on the assumption that colleagues know what they are doing. However, that does not allow for human error or deliberate corner-cutting, nor does it prevent technical debt accruing because developers are under pressure to get work done as quickly as possible. It is also unprofessional: skimping on a code review is simply avoiding the professional responsibility to produce work that is as good as possible. The last two points emphasise the community aspect of code reviews. As a member of the organisation’s professional community of software engineers, the individual developer needs to take an active role in enhancing the quality of the output of the whole team.

A formal approach to code inspections was defined in the 1970s by Michael Fagan for IBM. Some variations exist, but in general a Fagan inspection is quite a cumbersome and time-consuming process involving a formal meeting and several people in different roles. However, it does have the advantage of facilitating the collection of statistics related to the occurrence of code defects. This data can then in turn be used to improve processes and target developer education.

With the widespread adoption of an agile life cycle methodology and the use of code repositories such as GitHub, more lightweight review processes are typically preferred. Alls (2020) provides a very clear description of a typical code review which is the basis of the following notes.

Please read the section entitled Code Review - Process and Importance in the first chapter of

Alls (2020)

Please read the section entitled Code Review - Process and Importance in the first chapter of

Alls (2020)

Code review process overview

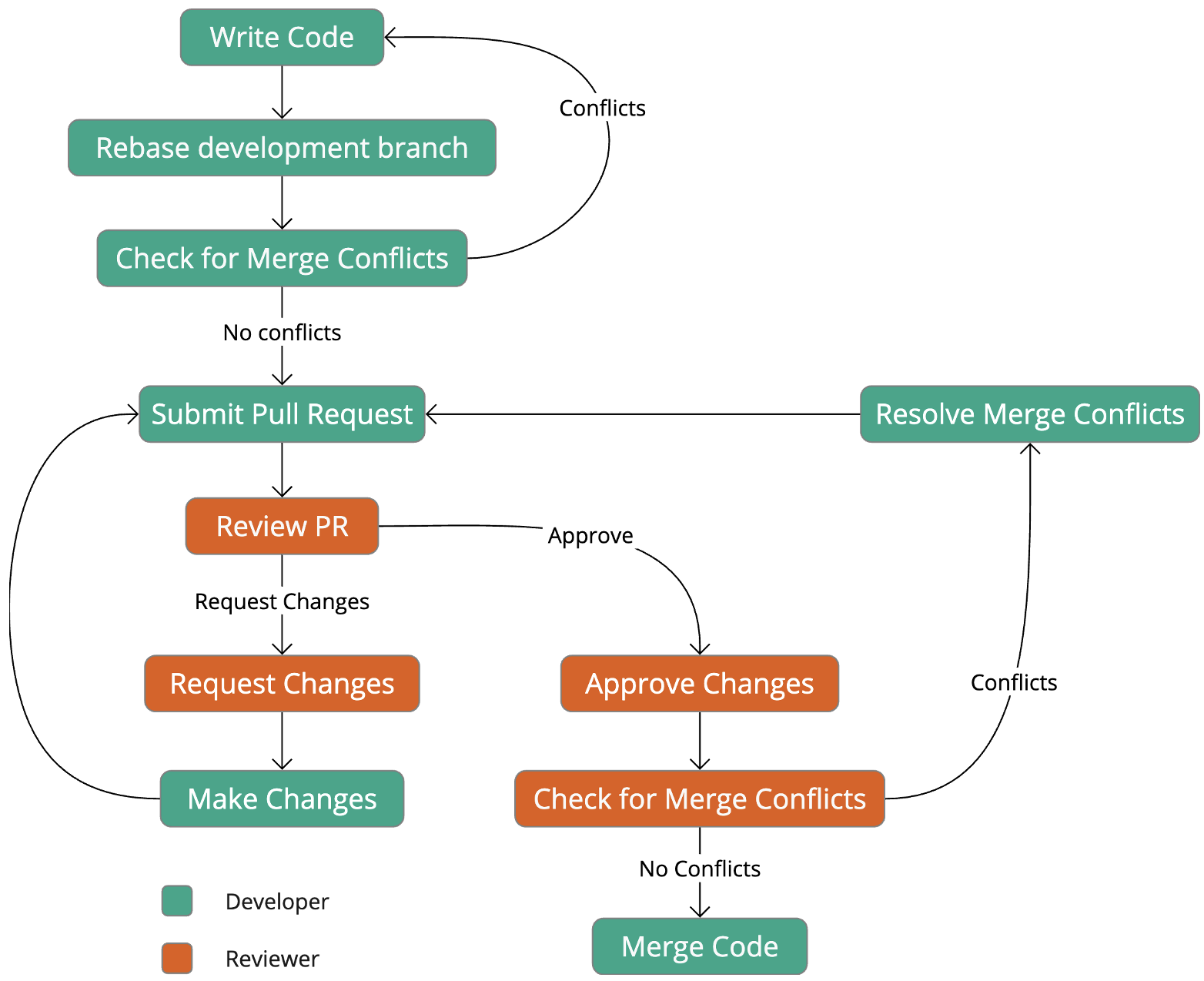

A code review happens between the completion a set of code changes and the merging of those changes into the main codebase. Before development starts, the developer will create a feature branch so that the related changes are isolated from the rest of the team. During development, there may be many commits until the work is finally complete. This will include the unit test code that the developer has created along the way. Once the developer believes that the changes are complete, they will make the final commit and create a pull request (PR). This is the signal for the code review to take place as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Preparing for a code review

In advance of issuing a PR, the developer should make sure that they have applied all the expected guidance and carried out the appropriate checks:

- Have you checked the wider impact of your code changes?

- Have you applied coding conventions for the language you are working in?

- Have you applied generic software engineering principles such as SOLID?

- Have you checked for code smells?

- Have you applied the principles of Clean Code?

- Have you created and run sufficient unit tests?

- Have you checked the hints provided by the static analysis tools in the IDE?

- Have you used the feedback available to sanity check your code?

It is considered good practice for a developer to rebase their development branch onto the main branch(or the target branch) to check for merge conflicts before issuing a pull request. Rebasing helps ensure that the development branch is up-to-date with the latest changes from the main branch and resolves potential conflicts early, making the pull request easier to review and merge.

Fig. 3 illustrates a scenario where a developer is working on a feature. In parallel, other developers merge changes a, b and c into the main branch. Because this could cause merge conflicts, the developer rebases their development environment before creating the pull request. Any conflicts can then be fixed in advance. The developer “cherry-picks” the latest commit from the main branch, hence the icon in the diagram.

---

title: Rebasing

---

gitGraph

commit id: " "

commit id: "Checkout"

branch feature

checkout main

commit id: "a"

checkout feature

commit id: "Commit 1"

checkout main

commit id: "b"

checkout feature

commit id: "Commit 2"

checkout main

commit id: "c"

checkout feature

cherry-pick id:"c" tag: ""

commit id: "Fix conflicts"

checkout main

merge feature id: "Merge"

Fig 3: Rebasing

Being the reviewer

As the reviewer, you are acting as a technical authority. You need to exercise your own knowledge of good coding practices and agreed conventions, and you need to be prepared to complement your existing knowledge by using appropriate reference material. Remember that the purpose of the code review is to enhance the quality of the code and for all those involved to learn from the exercise.

The best way to start a code review is to clone a copy of the code you have been asked to review. That will allow you to check that it runs as expected, that the tests all pass and there are no conflicts with the main branch. You should also run through the same set of quality criteria as the developer uses before creating the pull request (see above).

When providing feedback to a developer, it is important to be tactful and constructive. While amusing, the xkcd cartoons on this page and elsewhere illustrate exactly how NOT to word your feedback. Again, remember that the process should be constructive - creating resentment through undiplomatic feedback is not the way to enhance the overall performance of the team.

Collaborative platform like GitHub allow the reviewer and developer to have a conversation around the pull request. This is a flexible arrangement that allows for the fact that the points raised by the reviewer are not always black and white, and it may be necessary to exercise judgement and negotiate the appropriate solution.

Responding to change requests

If the reviewer requests changes during a code review, the developer should make the changes, test them and commit them to the branch associated with the pull request. It is good practice to add to the pull request conversation on GitHub or an equivalent platform. GitHub also allows the developer to formally request a re-review by using the options in the sidebar of the pull request page.

Performing the merge

Fig. 2 shows the merge step as the developer’s responsibility; however, either the developer or the reviewer can be responsible depending on the project’s workflow and team preferences. Both approaches have advantages, and the decision often depends on the specific context of the project.

| Who Merges | Advantages |

|---|---|

| Developer | <ul><li>Greater control and accountability</li><li>Can handle last-minute changes or conflicts</li><li>Faster, smoother development flow once the code is approved</li></ul> |

| Reviewer | <ul><li>Final quality assurance before the merge</li><li>Clear separation of duties between coding and codebase maintenance</li><li>More objective decision-making regarding merge readiness</li></ul |

In smaller or more agile teams where the developer owns the process it is more common for the developer to perform the merge as shown in Fig. 2. The reviewer approves the changes, and the developer merges the code after addressing feedback.

In more formal settings, or where extra control is needed, the reviewer will handle the merge after confirming that everything is complete, passing tests, and conflict-free. This is typical in larger teams with stricter processes.

Further reading

- GitHub pull request documentation

- Software inspections O’Regen, 2022, Ch. 7

- Modern Code Reviews — Survey of Literature and Practice (Badampudi et al., 2023)

- A Faceted Classification Scheme for Change-Based Industrial Code Review Processes (Baum et al., 2016https://doi.org/10.1109/QRS.2016.19)