Table of Contents

Environments

We have already discussed distributed version control where each developer has their own clone of the shared repository. Here, we introduce a related concept that also involves multiple copies of the codebase.

An environment is the working context of a software system. The term is widely used and it is important to understand its full implications. The major distinction is between the production environment (also referred to as the live environment) where a system is in actual use, and the development environment where software developers are making changes. As the software system evolves over time, code changes will be introduced into the production environment, but this has to be done very carefully to avoid any disruption to the users. The development environment replicates the production environment including code and supporting infrastructure such as databases. Because each member of the development team will be working on different changes to the codebase, each one will have their own development environment. This is an important detail: the development environment is not shared - each member of the team has their own copy which includes the last known good configuration of the codebase, plus the changes they are currently working on.

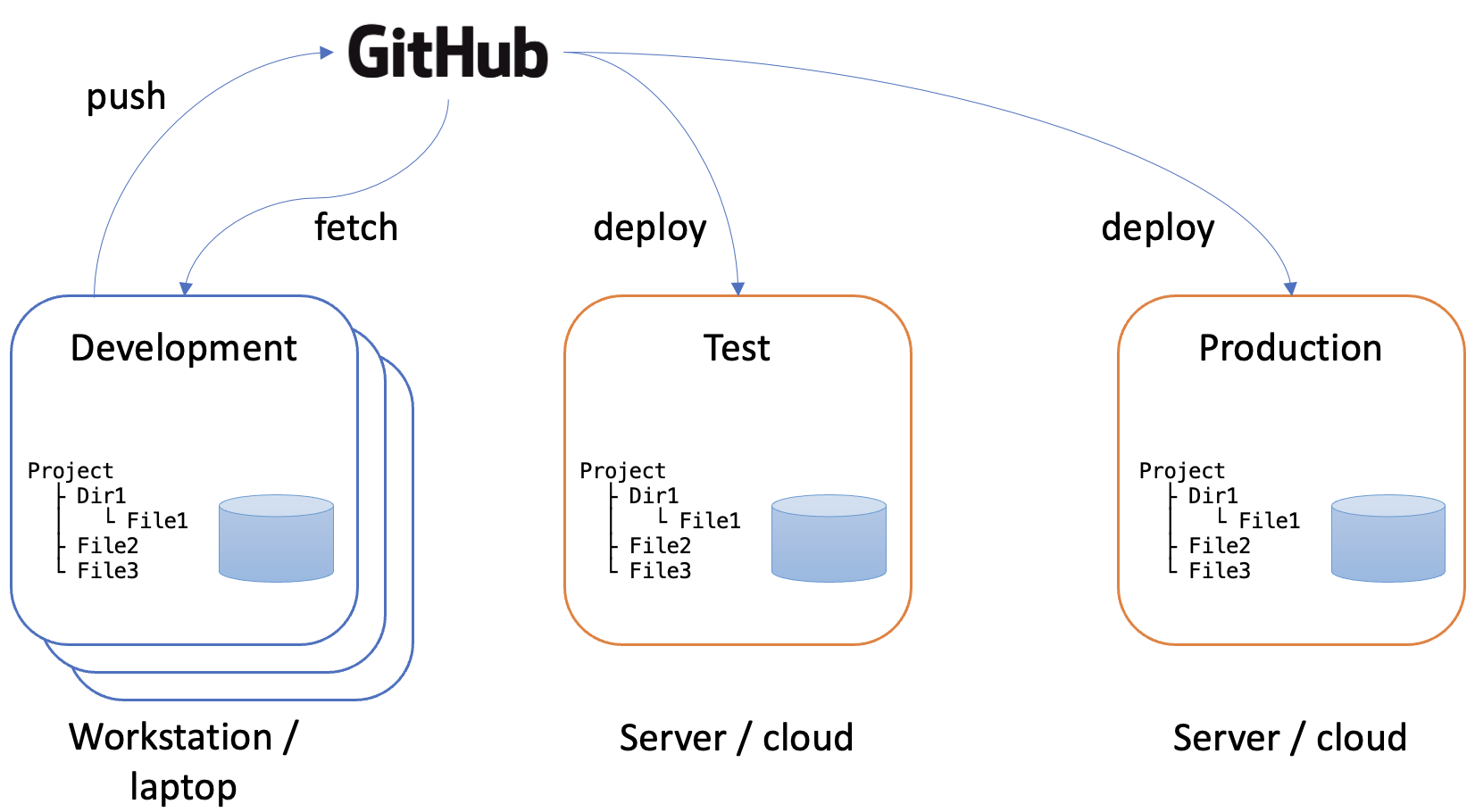

Fig. 1 shows the three main types of environment:

-

Development Environment

The development environment is where developers write and test code locally. It’s a sandbox for building new features, fixing bugs, and experimenting with changes. This environment mirrors the structure of the production environment, but it often includes developer tools, debuggers, and local configurations. Changes in this environment are frequent, and the code is not yet stable.

Purpose: Code creation, local testing, and debugging.

-

Testing Environment (QA/Staging)

The testing environment (sometimes referred to as QA or staging) is used for more rigorous, controlled testing before deployment. This environment closely resembles the production environment but is not customer-facing. It is where integration tests, unit tests, and user acceptance tests (UAT) are performed to ensure that the software functions as expected. The testing environment allows teams to catch bugs or inconsistencies without affecting users.

Purpose: Quality assurance and verifying software performance, functionality, and stability.

-

Production (Live) Environment

The production environment where the final, stable version of the software is deployed for end users. This is the environment that users interact with, and it needs to be highly reliable, secure, and optimised for performance. Code deployed to production has passed all necessary testing stages, and any issues here could impact users directly.

Purpose: Deliver the final product to end users in a stable and secure environment.

Repository management tools such as GitHub are excellent tools for managing the synchronisation of the various environments in use. Once developers have completed the changes they are working on, they push the code to the repository. Once any quality assurance procedures have been completed, the code can then be deployed to the production environment. Fig. 1 illustrates this and also includes a test environment where integrated code can be tested before deployment. Like the production environment, the test environment is a shared instance of the code that is hosted on a server or on the cloud. Development environments, in contrast, are located on the workstation belonging to the individual developer. In order for their personal development environment to be kept up to date, developers need to fetch changes from the repository on a regular basis. Typically, this is done just before starting a new development task. During work on a task, it is important that developer’s working environment remains stable. Changes from other developers are only introduced between one task and the next.

Other types of environment

Having a clear understanding of the way environments are used within a project is vital to ensure that things continue to run smoothly. Many steps in the process of code deployment and synchronisation of environments can be automated and in the majority of cases there will be no problems. However, no system is perfect and when things go wrong, it is up to the team to sort them out. Some steps such as the synchronisation of the development environment remain the responsibility of the individual developer. A good familiarity with some basic concepts is therefore required. The remained of this section recaps on some concepts that have almost certainly come across before. They bear repeating here though because they are fundamental to the way software systems are developed and managed, and having a clear picture of what is going on behind the scenes helps to understand processes more clearly and gives you greater control over them. If you are comfortable working at the command line, you will have no difficulty with the ideas summarised here. Although the majority of our interactions with computers now take place via a graphical user interface (GUI), the files that make up an application are still arranged in a hierarchical tree structure. This has been a constant feature of operating system design since the introduction of Multics in 1967. While a GUI is convenient, it is much less efficient that using the command line, provides limited control and has its own learning curve.

In a complex or sensitive context, it may be advantageous to differentiate between a test environment and a staging environment. A staging environment is a controlled, production-like environment used to test software just before it is released to production. It closely mimics the configuration, data, dependencies, and infrastructure of the live production environment, providing a space to validate that the application will function correctly for end users. In staging, teams can conduct final tests, such as end-to-end testing, performance testing, and user acceptance testing (UAT), to confirm the software’s stability, functionality, and readiness for release. The purpose of the staging environment is to simulate real-world conditions as closely as possible, allowing teams to catch and address any last-minute issues that might arise when the software is deployed to actual users.

An integration testing environment, in contrast, is used earlier in the development process to test how different components of an application work together. It allows developers to verify that various modules, services, and external dependencies (like databases or APIs) integrate properly. Integration testing environments may not always match the full configuration of production; they may lack certain data, security settings, or infrastructure setups that are present in staging. The goal of integration testing is to ensure that each part of the application communicates and functions correctly within the system as a whole.

While both staging and integration testing environments are used to validate the application, they serve different purposes and occur at different stages in the pipeline. The integration testing environment is used to verify that components work together correctly, often as a step within a continuous integration pipeline, whereas the staging environment is typically the last testing environment before production, providing a final check under conditions that closely replicate those in production.

Deployment

Deployment in the context of software product development and maintenance refers to the process of making an application or software system available for use by deploying its code to a specific environment. This can involve moving the software from development (where it is built and tested) to a production environment (where end users interact with the application) or to intermediate environments like testing or staging for quality assurance.

Deployment is a crucial step in the software development lifecycle as it takes the software from a development state to an operational state, making it accessible to users or testers. It typically includes installing the software, configuring the environment, updating databases, ensuring compatibility, and preparing the system for user access. These operations can be performed manually or they can be automated using continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD). Both strategies have their advantages and disadvantages:

Manual Deployment

Manual deployment refers to the process where developers or DevOps engineers manually execute the steps required to deploy code to a test environment, such as copying files, setting up configuration files, running deployment scripts, or issuing server commands.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Control: Manual deployment provides developers with complete control over each step of the process. This is useful when deploying small changes, troubleshooting specific deployment issues, or handling custom or ad-hoc deployment needs. |

Human Error: Manual deployment is prone to mistakes, such as missing steps, misconfiguring settings, or issuing incorrect commands. These errors can lead to failed deployments, issues in the test environment, or difficulty reproducing the same deployment steps. |

| Flexibility: Manual deployment allows for last-minute changes or specific adjustments based on the unique needs of each deployment, making it more adaptable for testing experimental features or configurations. |

Inconsistent Process: The manual approach can lead to inconsistencies between deployments, as different team members may execute the process differently each time. This lack of standardisation can introduce errors that are difficult to trace and resolve. |

| Learning Opportunity: For developers and operations teams, manual deployment can be a valuable learning experience, offering insights into the deployment pipeline and helping them gain deeper knowledge of the system’s underlying infrastructure. |

Time-Consuming: Manual deployment can be slow, especially when changes need to be deployed frequently or across multiple environments. Each step must be performed manually, which is labor-intensive and inefficient for teams aiming for rapid iteration. |

| Scalability Issues: As the project grows, manual deployment becomes less feasible. Coordinating deployments across multiple environments and handling larger, more complex systems manually becomes increasingly difficult and error-prone. |

Automated Deployment

Automated deployment uses scripts, configuration files, and tools like CI/CD pipelines (e.g., Jenkins, GitHub Actions, GitLab CI) to handle the deployment process automatically. This includes everything from packaging the code to deploying it to the test environment without human intervention.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Consistency: Automated deployments ensure that every deployment follows the exact same process, reducing variability and errors. This consistency is especially important in a test environment where you want reproducible results across deployments. |

Initial Setup Complexity: Setting up an automated deployment pipeline can be complex and time-consuming. It requires careful configuration and integration with the development pipeline. The initial effort may be significant, especially for smaller teams or projects. |

| Speed: Automated deployment significantly reduces the time required to deploy code. With a single click or trigger, code is deployed, reducing the manual effort involved and allowing for more frequent deployments, which is crucial for continuous testing. |

Less Flexibility: Automated deployment systems follow predefined steps and may not offer as much flexibility for handling last-minute changes or special cases. Although it is consistent, making quick adjustments on the fly can be more difficult without modifying the automation scripts. |

| Reduced Human Error: Automation eliminates the risk of manual mistakes like skipping steps or incorrect configurations. Since the deployment process is predefined, it reduces the likelihood of deployment failures caused by human oversight. |

Maintenance Overhead: Once automated pipelines are set up, they need to be maintained. Changes in the build or deployment process require updates to the automation scripts, and any issues with the pipeline itself can delay deployments. Additionally, ensuring that automation tools are kept up to date ca n add overhead. |

| Faster Feedback Loop: Automated deployment enables faster deployments to test environments, which speeds up the feedback loop. This allows developers and testers to quickly see the effects of new changes, leading to quicker identification of bugs and more rapid iteration. |

Learning Curve: For teams unfamiliar with CI/CD tools or automation, there can be a steep learning curve to understanding how to set up, manage, and troubleshoot automated deployments. It may require specialised skills, particularly for smaller teams. |

| Easier Rollbacks: Automated deployment processes often include rollback procedures, making it easier to revert to previous versions of the code if something goes wrong during the deployment, ensuring the stability of the test environment. |

|

| Scalability: As the project grows, automated deployment scales well across multiple environments and large systems. It ensures that the same deployment process can be replicated efficiently across multiple teams and environments. |

The choice between manual and automated deployment for a test environment depends on the complexity of the project, team size, and the frequency of deployments. Manual deployment offers control and flexibility but comes with a high risk of human error and inefficiency, especially as projects grow. Automated deployment, while requiring upfront investment and setup, provides speed, consistency, and scalability, making it ideal for projects with continuous integration and rapid testing needs. For most teams aiming for efficiency and scalability, automated deployment is the preferred approach, especially as they grow and require more frequent releases.